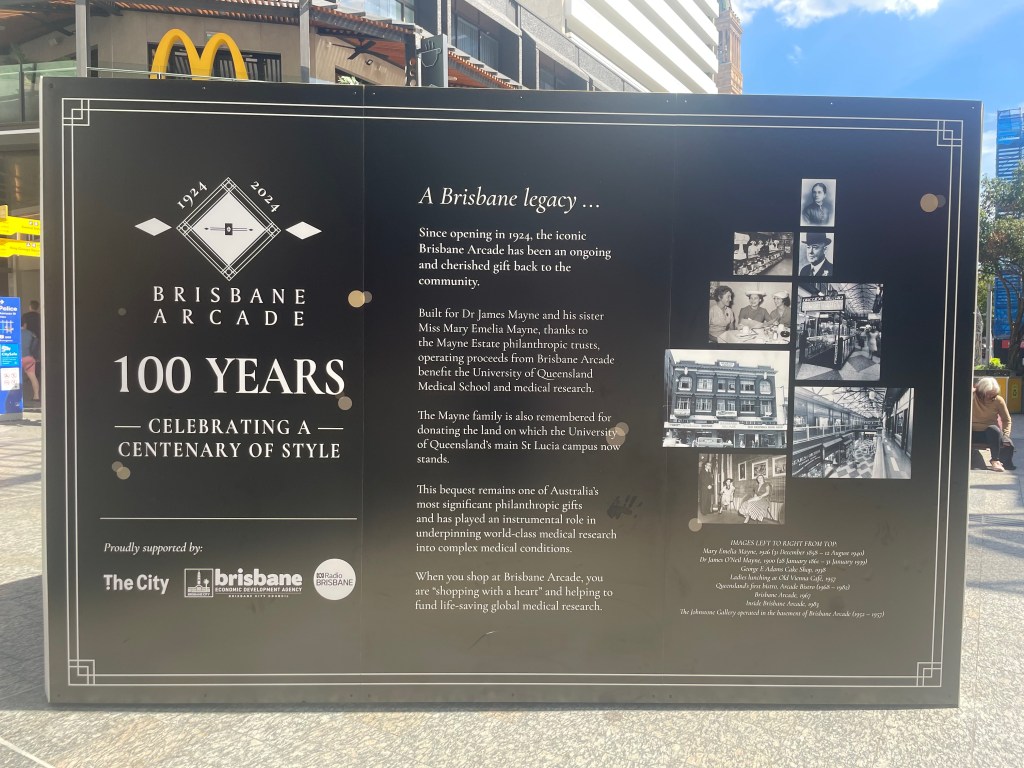

This year the wonderful Brisbane Arcade celebrates the 100th anniversary of its opening!

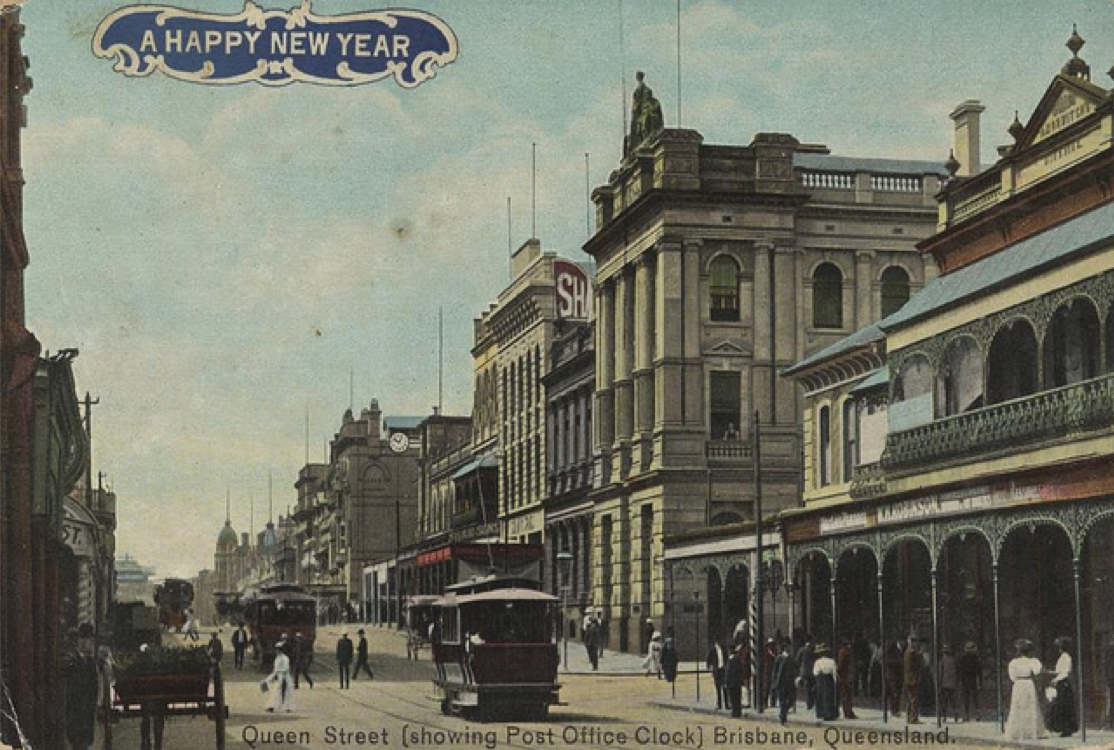

In February 1924 Brisbane’s Daily Mail celebrated the progress of the city through the many new buildings constructed over the previous 12 months. Only five years after the end of World War I, the enthusiasm for improvement, demolition of the old city and construction of the new was felt throughout Australia.

In Brisbane, this included the new Brisbane Arcade ‘of brick, with modern shops and plate-glass windows, this is considered equal to the best Sydney and Melbourne arcades, … [which] cost close upon £70,000’ (5 February 1924, 11).

A similar refrain to stories written for seventy years about arcades in Australia – comparing them to those in Britain, Europe and the United States and equating them with urban progress – is to be found in the stories surrounding this new example:

The arcade, leading from Queen to Adelaide streets, is an attractive addition to the city’s architecture. Arcades are a feature of most large American, Continental and English cities—the one now in the course of construction may one day become the Burlington of Brisbane.

Daily Standard, 3 January 1924, 7.

The Brisbane Arcade has delighted generations of Brisbane residents and visitors throughout the years. I remember walking through as a young child, thinking what a magical place it seemed to me – particularly the Darrell Lea chocolate shop!

As a teenager, it became a regular thoroughfare as I made my way to meet friends at the Hungry Jacks on the corner of Queen and Albert Streets (the regular meeting spot for generations of Brisbane kids). When I started my first job – Bookworld in the Myer Centre – at the age of 16, it again became my route to and from Central Station. It always seemed quite glam and very expensive at that time in my life but still endlessly fascinating.

Being originally an ancient historian, I sadly didn’t pay much attention to Brisbane’s heritage buildings until a few years after I moved to Sydney and morphed into a museum professional working in Australian history and heritage. It once again became a site that I visited and wandered, now taking more scholarly notice of its architecture and stories.

My PhD thesis on Australian arcades was originally planned to look at those built into the 1920s, including this wonderful arcade, the Johnston Arcade in Terang, Victoria, and the many examples built in regional towns in the early twentieth century. But the sheer proliferation of arcades built in this period meant I had to restrict my study to the five decades from 1853 (the first arcade built in Australia) to 1901 (the year of Federation).

Despite having to move away from this period, I still wanted to hear more about the stories of this building, which has always been a special place for me. This year I’m able to do that, as a Griffith University Harry Gentle Resource Centre Visiting Fellow. After a bit of a hiccupy start to the research a couple of months ago, I’m back in Brisbane beginning the project in earnest.

The work focuses on women business owners who occupied shops in the nineteenth-century Queensland arcades, focusing on businesses present from the 1870s to 1920s. I’m hoping to uncover the histories of these women: where they came from, how they financed their businesses, what motivated them to open their own establishment, what the experience was like for them, where they got their stock from, the networks they leveraged to do all of this, what happened to them after they left the arcades and, generally, to bring their stories to a broad audience.

At the end of the research, there’ll be a public talk, a website, a journal article, and a couple of conference presentations, all talking about these women. It will also contribute to a chapter in the book I’m writing based on my PhD thesis.

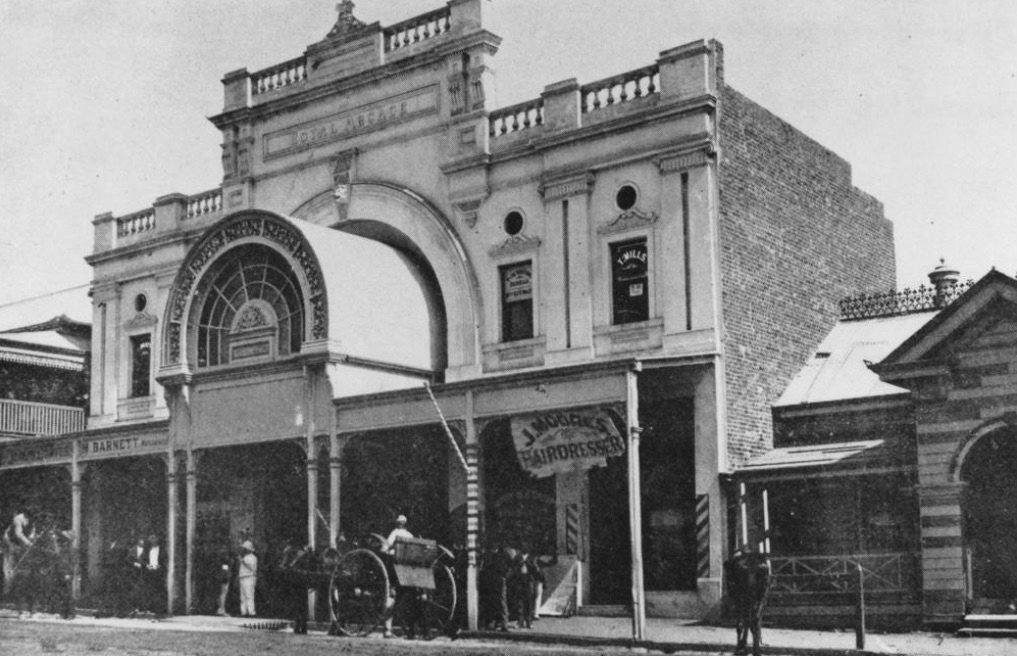

Brisbane Arcade was in fact built nearly 50 years after the city’s first example, the Royal Exhibition Arcade, down the road on Queen Street, and its successor, the 1885 Grand, straddling the corner of Queen and Edward streets (Tattersalls Arcade today sits on its footprint). Also earlier in Far North Queensland were the Royal Arcade in Charters Towers, built in 1888, and the 1901 arcade built as part of the Townsville Municipal Council buildings in 1901. For more on these earlier arcades, you can see my discussion of them in some earlier blog posts.

While I’m technically not researching the 1920s arcades, I likely will research the Brisbane Arcade for the project because I’d really like to compare both the usage and representation of this arcade with its nineteenth-century predecessors. We’ve already seen above in the list of store owners, many more shops aimed at women customers than those earlier examples. I also suspect when I look at the percentages, there will be a greater number of women owners as well. Many of those discussed above were at least run by women and there is a high likelihood many were owned by them as well.

With the 100th Anniversary celebrations, this week seemed an auspicious time to start on my research, and I’ve done a little on the Brisbane Arcade over the past few days, looking at newspapers and other sources.

Like a number of earlier examples, the Brisbane Arcade had a woman owner: Mary Emilia Mayne and her brother, Dr James Mayne, commissioned architect Richard Gailey Jr to design the building, with construction beginning in 1923. The Maynes were significant benefactors in Brisbane, helping to establish the University of Queensland Medical School at Herston and, in 1926, the land at St Lucia, where the main university campus is still located today. On their deaths, in 1940 and 1939 respectively, they left the proceeds of their estates in trust for the medical school, including the income from the arcade.

Nearly two months after that first article in the Daily Mail, the same newspaper informed their reader about some of the businesses about to open there (30 March 1924, 6). These included a wide variety of women’s clothes and accessories shops such as the Arcadia Shoe Salon; Myrtle Power Salon, selling frocks and table linens; Luxor Shoe Store; Miss Morrie McLoughlin, who sold frocks and gowns; Dulcie Decor’s frocks and wraps; Frank Brennan and Miss Brennan, tailoring and ready-to-wear for women; Jenny Salon, run by Esme Davis [or Davies], high-class costumier; SB Heiser, fine jewellery; Searl’s, ‘well-known Sydney florists’; The Women’s Exchange, with knickknacks and lingerie; and Britton and Williams Cutlery Co.

Unlike the arcades of the nineteenth-century, which aimed at a diversity of businesses to attract both women and men, the Brisbane Arcade seems to have focused quite closely on shops that would attract women clientele.

There is a distinct divide in the March article between the relatively feminine boutiques and the seemingly more masculine real estate agents and brokers and so forth. This may have reflected the changing idea of who a shopper was expected to be, or who the advertising and retail industries were targeting as their audiences, and the emphasis on shopping as a woman-centric pastime.

Looking at the Wise’s Directory for 1924-5 demonstrates that this article gives a good overview of the tenants, but mainly those on the ground floor. There were several other businesses there also, including refreshment rooms: Mrs Edge’s White Swan Café and a restaurant run by the Misses Alford and Watts.

On the first floor this continued with more dressmakers and similar businesses aimed at women, as well as the workrooms of some of the stores on the ground floor such as those of Jenny Salon and Brennan & Co. However, there were quite a few others that would have attracted male visitors.

These included a number of agents, also listed in the newspaper article, on this level (accessed via the balcony that runs along the entire outline of the void). This included AJ Hoye, estate agent; DB McCullough, real estate; John McCormack, house, land and business agent; and Allsop and Taylor, real estate. Also to be found upstairs were Cranfield’s Sports Depot, the Committee of Direction of Fruit Marketing, the Queensland Lawn Tennis Association, the Financial Aid Co and a number of (likely men’s) tailors on the first and second floors.

It seems then that there was an apparent spatial divide along gender lines in the building, at least initially. The ground floor was largely aimed at women clientele or more ‘feminine’ pursuits and interests, while the upstairs tenancies were those more traditionally associated with males or a mixed clientele. This is not to say that men didn’t accompany their female relatives to downstairs stores or food outlets, but that the division of interests by gender was apparent.

Of relevance to my current research project, one noticeable difference between nineteenth-century arcades and the Brisbane Arcade appears to be the real shift in gender balance of those running businesses. Here we see an overwhelming majority are run by women, unusual for the arcades of the previous century, particularly those in Brisbane. We do see women-run businesses to varying degrees in those earlier arcades, but they are by no means in the majority and, in Brisbane, there are in fact far more men listed as tenants.

I’m looking forward to exploring more about these changes over time, and when, where and why differences might occur, including looking through newspapers and perhaps business records of shops or business associations, when I can find them.

For the next fortnight, I’m working in the State Library of Queensland and the Queensland State Archives to start to unpack the stories of the Queensland arcades and their businesswomen and I’m very excited to bring you along with me on this research journey. I’ll be posting on my Instagram a bit along the way, so please join me!

Meanwhile, there is loads of stuff happening to celebrate the Brisbane Arcade’s 100th birthday. They have a great range of historical stories about the building on their website, including visitors’ memories of the arcade over the years. This Friday, 19 April, will see a special celebration on the Queen Street Mall, outside the building, with a radio broadcast, special gifts, entertainment, cake (!) and more during the day to celebrate the occasion.

You’ll definitely see me there and, while Darrell Lea is sadly gone, I’ll be stopping by their successor, the Noosa Chocolate Factory. Yum!