Welcome back! This week’s post started off as a very quick musing on something I became interested in during my thesis but had ended up as a dead end. So, I very quickly wrote a ‘short’ post on it, thinking I might just think through some of the issues. Of course, this short post is now a bit of a long read, as I keep thinking of further avenues to investigate and it’s turned out much longer and more intricate than expected. It is now something of a thinkpiece on my own history practices as well as a specific site. But I hope it’s enjoyable for its dive into mid-1800s Melbourne during the goldrush years, layers of urban history, and some of the sources that we look at when doing this type of research.

During the research and writing of my thesis, there were a few arcades that bothered me. With some I couldn’t figure out if they’d been arcades in the nineteenth-century or had been modified in the twentieth. Still others bore the name ‘arcade’ and were mentioned in the newspapers but I was uncertain, if there were no descriptions, that they were the type of arcade on which I was focusing: with shops running along a central promenade (and usually a glass roof). In colonial Australia, the word ‘arcade’ was used for these types of buildings but also others, including large furniture or mixed business shops and, famously, for the Coles Book Arcade in Melbourne.

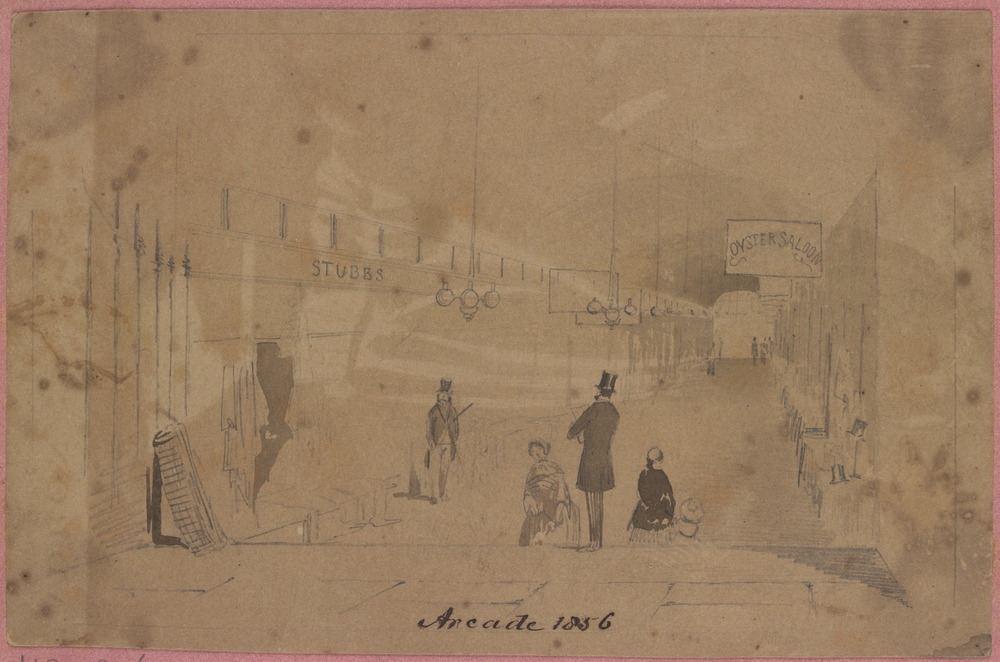

And then there was the Victoria Arcade in Melbourne. Early on in the research I came across this beautiful image (above) in the State Library of Victoria, depicting a beautifully ornate arcade, with some inscriptions.

Victoria Arcade, now erecting in Bourke Street East

Wharton & Burns Architects & Surveyors

30. Collins Street MelbourneJohn Black, Proprietor

J.S. Campbell & Co., Lithographers

It also has a small ‘handwritten’ signature identifying the artist: STG – for Samuel Thomas Gill – and the date [18]53.

Three years later, ST Gill, would go on to do a small sketch of the Queens Arcade and was to become a well-known and prolific chronicler of goldrush Victoria, including its urban environments. Even later, he would do another lively street scene in front of the Royal Arcade, completed in 1870, also on Bourke Street.

Possibly a companion or slightly earlier piece to that of the Victoria Arcade is another lithograph by Gill (below), also dated 1853, of Black’s Tattersalls Horse Bazaar on Lonsdale Street.

These two artworks demonstrate a grandeur and elegance that Melbourne entrepreneurs and officials were at pains to emphasise during this period, as they tried to ‘improve’ and ‘civilise’ the fledgling city. In reality, Melbourne at the time was far from this, with a rapidly expanding population due to the goldrush. Many still lived in the tent encampment south of the Yarra and other temporary structures, as well as portable (kit) iron and wood buildings imported from England, were erected to provide residential premises; the city was a building site, as the construction tried to catch up with the needs of the population.

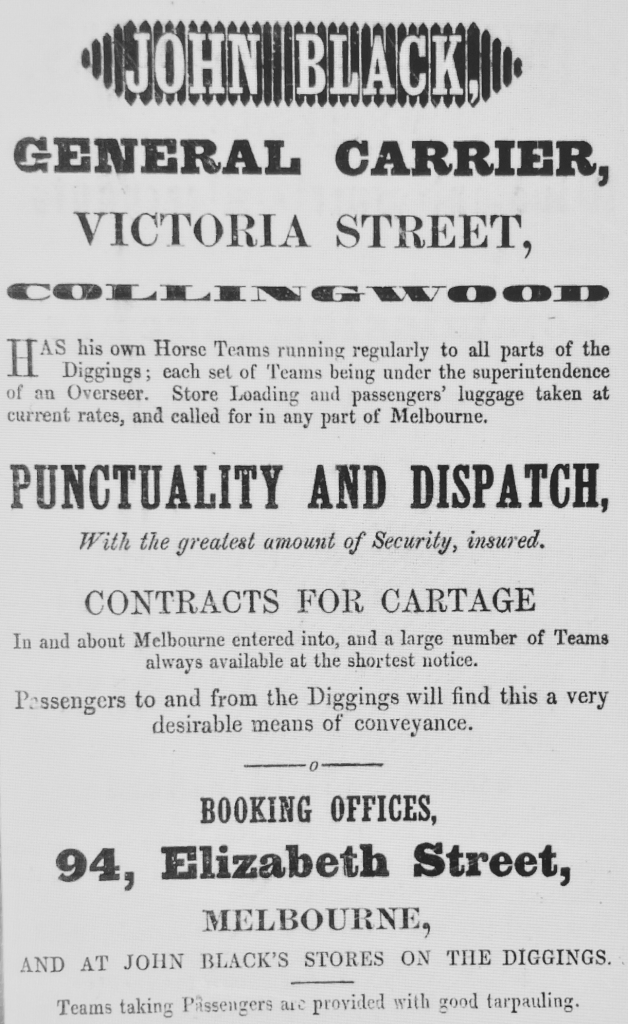

Seeking to take advantage of this was entrepreneur John Black, born in Lancashire of Scottish ancestry. He arrived in Australia around 1852, likely drawn by the lure of the goldrush. Having worked for a London merchant prior to emigration, he promptly set up carrying goods between the goldfields, Geelong and Melbourne (Gibson-Wilde, 25). An advertisement in Pierce’s Commercial Directory from 1853 shows that he also had ‘stores’ on the goldfields, likely supplying a wide mix of needs for miners including food and equipment.

Goldrush immigrants often made more from businesses such as this than they ever would from gold and it appears that Black made a solid fortune in a short time. On 1 November 1853 John Black (as well as a man named Edward Gilbert) obtained an auctioneer’s license in Melbourne, likely in preparation for his two new ventures: the horse bazaar and the arcade.

Black probably commissioned Gill to make the images of Tattersalls and the proposed Victoria Arcade when one or both buildings were in the planning stages. The Argus reported on the completed horse and cattle bazaar on 14 November 1853, noting it was an arcade-like structure “used for an hotel, livery stables, auction mart, cattle-yards, coach-house, warehouse for vehicles &c” (14 November 1853).

An advertisement from the Argus on 4 November 1853 tells us that plans for the arcade were publicly displayed in the finished bazaar for prospective tenants to view.

VICTORIA Arcade.—Parties requiring Shops in the new Arcade, Bourke street, are requested to apply early. The plans are to be seen at Tattersall’s Bazaar. Lonsdale street east. (4 November 1853, 8)

The Illustrated Sydney News told readers in greater detail about this planned urban enterprise:

COLONIAL ENTERPRISE.—Spacious as Mr. Black’s new Tattersalls, in Lonsdale and Bourke-streets, undoubtedly is, and creditable alike to the proprietor and the colony, it will be thrown completely into the shade by a new arcade which the same spirited speculator is about to erect as a continuation of the new Tattersall’s.

Immediately opposite, and running in a straight line, is the full acre allotment, the property of Mr. [O’]Sullivan, the timber merchant, and this gentleman has leased it to Mr. Black for eighteen years, at a rental of £3000 per annum. On this acre Mr. Black has bound himself down, in a heavy penalty, to erect an immense arcade, to consist of two-storied shops, forty feet high.

The two end buildings leading into Great and Little Bourke-streets, respectively are to be each four story houses; the whole is to be roofed with corrugated iron, and entirely finished by the 1st of April next. Every house is leased already at £250 a year (serving for both residence and business premises,) the tenants each paying down a bonus of £1000 on taking possession. This will probably be the most gigantic undertaking entered into by one individual south of the line. (26 November 1853, 4)

Until I found the Gill Victoria Arcade lithograph, my research suggested that no other building of this type was built in Melbourne between the Queen’s Arcade in 1853 and the Royal Arcade in 1869–1870 (one newspapers made a point of this lack when discussing the latter!).

An arcade named the Victoria – more properly the Victoria Arcade & Academy of Music – was later built on Bourke Street East in 1877, almost opposite the site slated for the 1854 Victoria Arcade. In addition to an arcade with shops, it included a theatre. This later became known as the famous Bijou, which ultimately had greater longevity than the arcade itself. While that is a story for another time, it confused me quite a lot when I found the 1853 Gill image. It was very common in nineteenth-century newspapers to not give a street address, so I wondered, was this an earlier iteration of that arcade? But it could not be as it was clearly identified as being on the opposite site of the street.

I then found a couple of newspaper reports in the 1850s that mention a Victoria Arcade as though it was completed: one year after it was first announced, we see a classified for a ‘Cook-shop to Let, with Fixtures Complete’ is identified as ‘next the Victoria Arcade’ (Argus, 10 November 1854, 3), while Chapman’s Music Warehouse is mentioned at Victoria Arcade a week earlier. Unfortunately, these seem to be simply mistakes of naming: Chapman’s, which was still in existence in the mid-1890s, was definitely located in the Queens Arcade, as many advertisements attest. It seems it would be an easy confusion, the Queen of the eponymous arcade of course being Victoria.

So what was happening here? Was the arcade built or not?

One fabulous source for identifying early buildings and their construction dates in Melbourne are the wonderful leather-bound volumes of building notices from the Melbourne municipal council, now held at Public Record Office of Victoria (PROV). They’re a little tricky to use and it doesn’t help that usually there often only a street name and not an address for these proposals, in the first two volumes at least.

When I delved into them (and it was wonderful!), I found some hints. In the first volume (1850–1853) I located a notice – 1118 for the year – ‘To build a Horse Bazaar’ on July 8 1853, with John Cotter named as builder for owner, John Black. On the next page, we are informed that works had commenced and the fee charged was £4.

But nowhere in late 1853 or early 1854 did I find a mention of a Victoria Arcade (although the Queens Arcade did appear in 1853). In the second volume, though, on 1 June 1854, Black’s name appears in the book at the head of another venture, with the notice of intent ‘to build a theatre’ on Bourke Street. This was the famous Theatre Royal, which opened very late in 1854, renowned in Melbourne until its last performance in the 1930s, but likely partly the causes of Black’s insolvency in 1855.

Looking at other evidence, it becomes clear that the theatre was in fact built on the site slated for the proposed the Victoria Arcade in the Gill image, only 12 months after initially announcing the construction of the arcade.

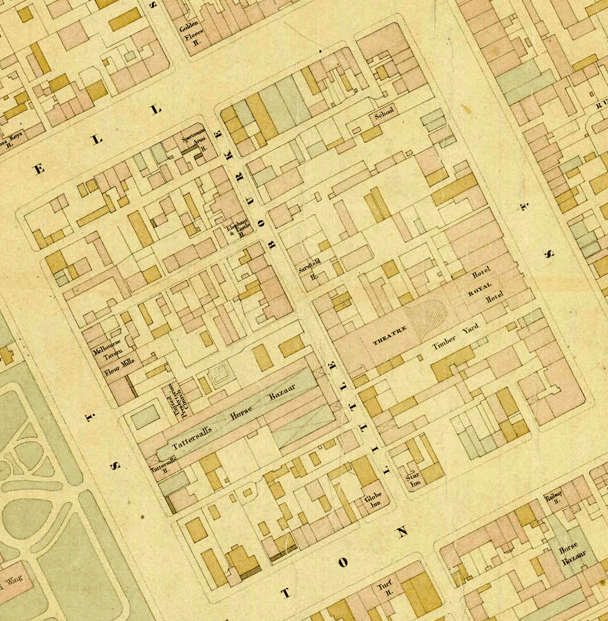

An amazing c1860 map (known as the ‘Bibbs Map’) has been digitised recently in super high res and added to the City of Melbourne’s wonderful mapping site, with plans and aerial shots of the city layered over time. In it we can see that the Horse Bazaar and Theatre Royal ran in a straight line from Lonsdale to Bourke streets, just to the east of Swanston Street. We also know from the Illustrated Sydney News article above that the Royal was located on the the block of land where the arcade was to be constructed.

An earlier version from c1856 above, is also available in high resolution at Public Records Victoria, showing both buildings in greater detail, and its history is discussed in my colleague Barbara Minchinton’s article in PROV’s journal, Provenance.

I’ve not yet located any article that indicates that any decision was made to abandon the arcade nor construct the theatre. Perhaps these will turn up one day – I’ve not given up searching but it’s highly likely Black did not want to make a pronouncement about the change in his plans.

One advertisement for the sale of a partially completed ‘New Theatre’ in October 1854 is likely the Theatre Royal, as is the call for tenders for the completion of a theatre in early December. But the first mention of it definitely as Theatre Royal that I’ve found so far in the papers is the announcement on 22 December for its opening the following day.

On 23 December the theatre opened but in an incomplete form, with just the entrance buildings and promenade entry completed. That day the Argus advertised the ‘GRAND OPENING of the Lower Saloons and Superb Entrance Hall to the New Theatre Royal, Bourke-street east’, featuring performers such as Mrs Hancock, Miss Octavia Hamilton and infant pianist Miss Minnie Clifford, and performances continued in the promenade – Black perhaps needing to recoup some of the money already outlaid on his building ventures.

Looking at commercial directories is also a way to trace the development of buildings in the city. State Library of Victoria (SLV) and University of Melbourne have the well-known Sands & McDougall directories online for a selected number of years from 1857 to 1974 but all are too early for this conundrum.

So, I visited SLV and the helpful staff in the Newspapers & Family History Reading Rooms to investigate the earlier directories – held on microfiche. In Joseph Butterfield’s directory for 1854 (which would have been prepared in late 1853 or early 1854), there was no evidence of Tattersalls or an arcade. But the former appears in the same directory for 1855, named Tattersal’s (sic) Repository and Tattersalls Hotel, as does the Theatre Royal at 73 Little Bourke Street East as ‘New Theatre and Hotel Building’.

It was in fact not until mid-1855 that the theatre was fully completed and finally opened on 16 July. A large article singing its praises appeared in the Argus the week before:

As this magnificent Temple of the Drama is announced to be opened for the first time on Monday evening next, a narrative embodying the history of the edifice, and a description in detail of what has already been effected, may be interesting. … Mr John Black … notwithstanding many impediments which have periodically opposed themselves to the work he took in hand, has now the satisfaction of seeing his design practically carried out. (10 July 1855)

The article praises Black’s vision for the theatre – completely omitting that the site had once been slated for an arcade only 18 months previously. It tells in detail of the architecture and fittings and compares the building to London’s Covent Garden and Drury Lane theatres and the expenditure of £60,000 in its construction (an amount equating to perhaps 9-10 million Australian dollars today).

So, why abandon the arcade idea? Did the cost of the building proposed in the first Gill image prove prohibitive? Did a theatre seem like a more secure return for Black’s outlay? Perhaps with the opening of the Queens Arcade in December 1853, there was insufficient interest in another similar edifice? Ultimately, it was probably a sound decision; the Queens was not a huge success and was converted to a hotel and dining rooms by around 1860, while the theatre lasted in some form for another almost 80 years.

Much of documentation related to the parcel of land since 1851, several years before Black built the theatre, are preserved in the Coppin Collection at State Library Victoria (SLV). Possibly one of the most famous nineteenth-century Australian actors and theatre entrepreneurs, George Coppin, took over the Theatre Royal from Black in 1856. The collection include leases and mortgages, not just for the theatre but also for the lots on which Tattersalls stood.

Prior to March 1854, fellow auctioneer Edward Gilbert took over Tattersalls from Black, possibly to free up funds for Black to build the theatre, and documents related to a mortgage between the two for that land and the Tattersalls business is also contained in this collection. They also show a number of varied interests in the theatre by a number of other Melbourne businessmen. These documents show and intricate and complex shuffling of money to try and finance new buildings in the rapidly growing city.

While the theatre itself was long-lasting, the financial woes of the colony likely caused issues for a number of those invested in both it and Tattersalls, including Black. The same article that praises the new building goes on to indicate that the financial troubles over the past year had made the work difficult. Following the exuberance of the first years of the Victorian goldrush, in 1854 a recession hit, causing significant unemployment (Broome 1984, 87), and this downturn seems to have been blamed for the slow construction of the theatre. As Dorothy Gibson-Wilde notes, several days later, Black was accused by letter writers in the Argus of underpaying workers and owing money to contractors (Gibson-Wilde, 2009, 108). But this was the least of Black’s troubles.

We can see from the documents at SLV that huge sums of money were involved in developing both Tattersalls and the Theatre Royal, and that they inevitably bankrupted several people involved with them. The original mortgage above, was in the amount of almost £35,000 that Gilbert would owe to Black, who had spent considerable money on the Tattersalls buildings, and the theatre purportedly cost £60,000.

Gilbert almost immediately tried to lease and then sell the Horse Bazaar and, by June 1855, its abject failure resulted in his insolvency. Losses on the Bazaar totalled over £13,000. In one insolvency hearing in November that year, the Commissioner noted:

the insolvent had placed the whole of his capital in the speculation of Tattersalls, which speculation had unfortunately turned out an entire failure. (Argus, 12 November)

At the same time, Black was also declaring insolvency. While this has been blamed on the expense of the building the theatre and the fact that Black probably wasn’t the best theatre manager, it certainly should also be attributed to the economic downturn. Gilbert’s insolvency report in fact made specific mention of

the period when the insolvent took possession of Tattersall’s Horse Bazaar. The colony at that time was in the very height of prosperity. Speculation and enterprise were driving men on to undertakings of inconceivable magnitude; and there is no doubt that the insolvent was inoculated with the spirit of the times, and with his capital at hand aspired to become the master of a building which presented at that moment a princely fortune. (Argus, 23 August 1855)

But it also seems that those with vested interests in the business blocked him from selling it to Coppin earlier, when he might have broke even. For several years, the shadow of the failure of Tattersalls and Theatre Royal, followed others – also resulting in the insolvencies of Gilbert and Black’s solicitor, Frederic Bayne, who had taken on Black’s interests following the latter’s insolvency, and of John O’Sullivan, to whom Gilbert’s mortgage from Black had been transferred in 1854 (and who is listed as Tattersall’s proprietor, together with E Gregory, in the directory mentioned above).

Black himself got back on his feet, becoming manager of the new Princess Theatre on Spring Street for several years. Later, he moved to Queensland, where he became the founder and first mayor of Townsville, before returning to England in the late 1860s and dying wealthy man in London in 1919 (Gibson-Wilde 1982, 2009).

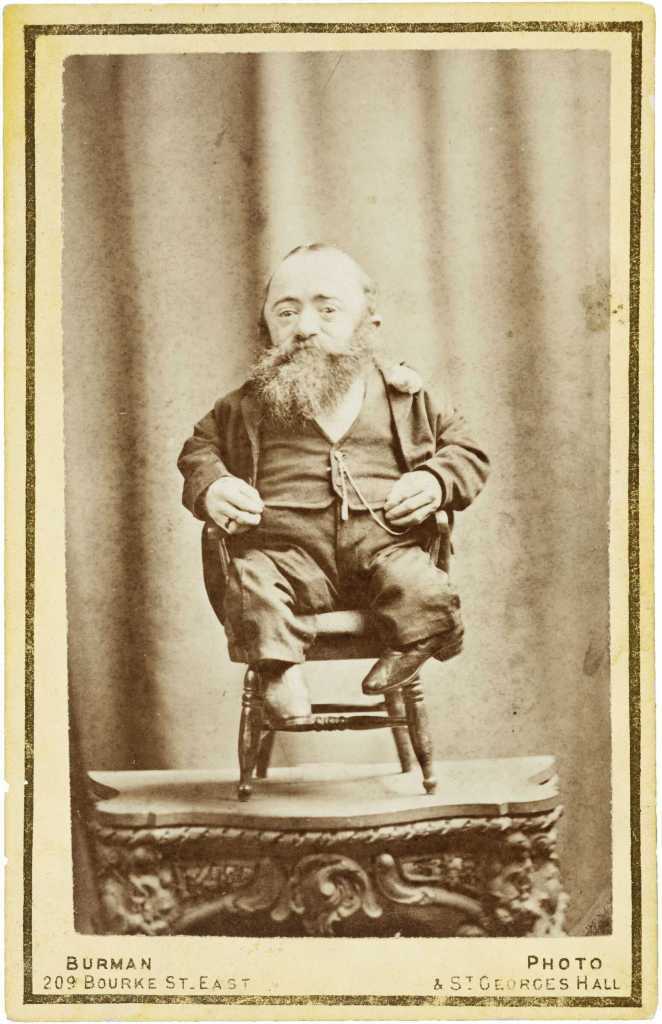

Despite these beginnings, George Coppin was to make a great success of the Theatre Royal. He put on successful entertainments there for the rest of the nineteenth-century. Although the 1854/5 version was destroyed by fire in 1872, Coppin rebuilt a newer and even more impressive edifice immediately after and the theatre remained a popular Melbourne entertainment spot until its demolition in 1933.

Reading between the lines of these articles, and their silences, does make me wonder if the façade buildings of the theatre were, in fact, originally intended as the front of the arcade, although with modifications to the design. If we look at the images of the original theatre, we see that similar arched windows/entries planned for the arcade are also seen in the theatre entrance building. The centre entrance to the vestibule also mirrors that of the arcade, but with a square rather than curved arch. It also has not only wooden doors on the vestibule entrance but iron gates similar to those planned for the Victoria Arcade and which were common to buildings of this type.

I’ve been pondering this possibility for a long time and have really not come to any concrete conclusions. There were always more and better documented arcades to discuss in my thesis. But this is another rabbithole that I’ve jumped into the last couple of weeks and has led me down an archival adventure to be sure!

Perhaps other sources will also give an idea, such as diaries or letters from the period. I’ll also potentially do a systematic read through the newspapers for this year, rather than simply doing keyword searches in Trove. A few issues arise with searching online newspapers that mean you’ll never be quite certain to capture everything. One is that you inevitably come up with thousands of many options when searching, especially for the word ‘arcade’ or ‘Victoria Arcade’ or even ‘Victoria Arcade’, ‘John Black’, ‘Bourke Street’. Another issue is that often the quality of the printing of some original papers means that the OCR (Optical Character Recognition) doesn’t recognise everything accurately (hence Trove has an army of volunteer editors to correct the final results).

So, that’s where I’m at with it right now with this work-in-progress. When I do a bit more digging, I may have an update.

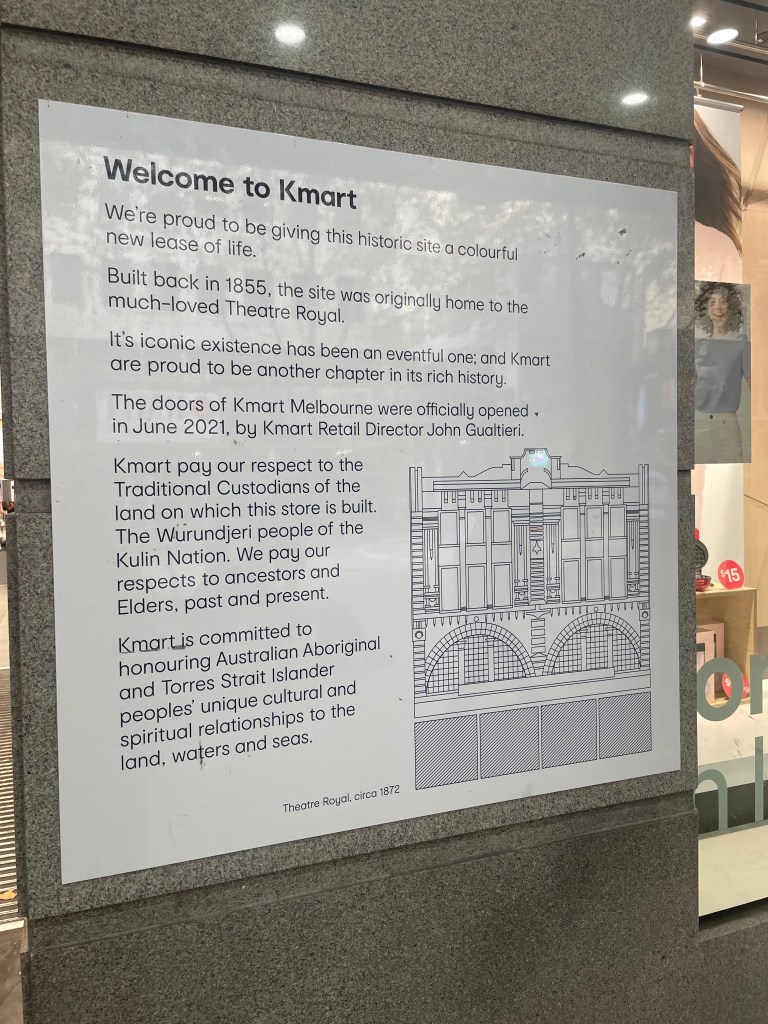

A postscript though: there is a twist in the fate of the site itself that might have had Black wryly shaking his head. After the Theatre Royal was demolished in 1933, the valuable site saw the construction of the large Mantons department store in modern Art Deco style. This business was eventually taken over by GJ Coles in the 1950s. The facade of Mantons was covered over and it was occupied by a succession of variety stores owned by the parent company of Coles-Myer : Coles Variety, then Target and, in 2021, KMart.

At some point during these changes, probably around 1994, renovations to the building included the formation of an arcade running through from Bourke to Little Bourke and, although modern and utilitarian, it runs just slightly to the left of where the promenade of Black’s planned arcade would have.