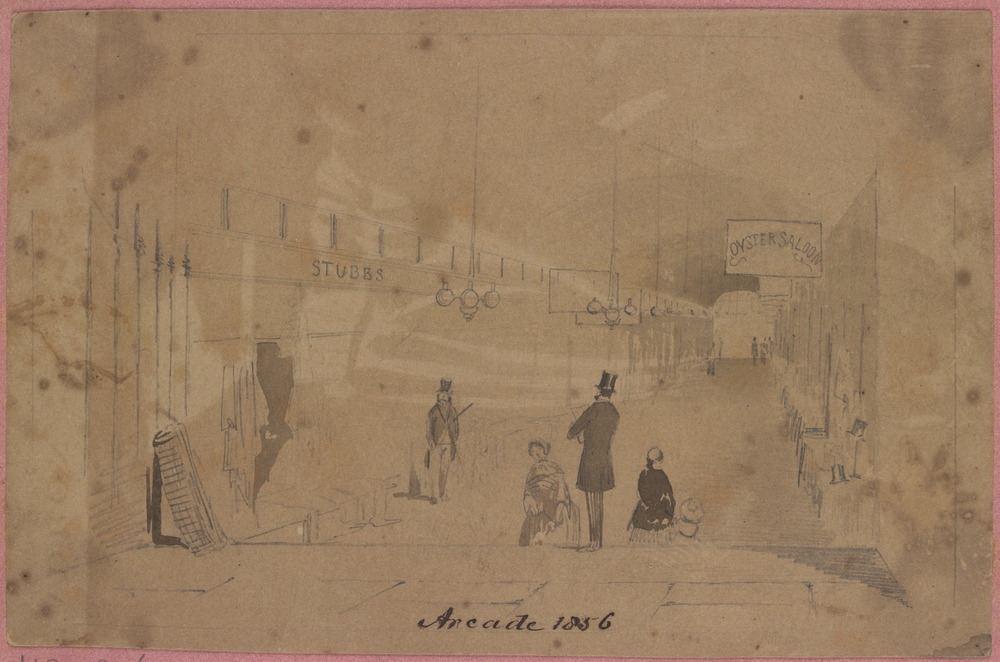

The Queen’s Arcade on Lonsdale Street in Melbourne, after renovations, reopened to great fanfare in March 1856, with a military band and a fountain of eau de cologne supplied by arcade fancy goods’ dealer Levy Bros, as well as

musical entertainments … varied by the performance of a powerfully toned apollonicon [a large barrel organ], which is intended in future to play at stated periods during the day, and thus prove a continual attraction to the passer-by to make use of this elegant avenue as a lounge

Age, 17 March 1856, 4

Arcades are often thought of purely as places of commodity exchange or places to eat and drink, with retail shops and tearooms often the focus of discussions both popular and academic. As I argue in my thesis, the arcades in fact reflected broader social and cultural aspects of urban life, with a wide variety of entertainments, including theatres, dance halls, hotels, balls and music in the promenades, and amusement parlours. As I note in Chapter Five, following James Lesh, arcades ‘catered for colonial Australian thirst for “amusements, performances and hospitality: novel forms of leisure and entertainment”[1] that were part of the global experience of modernity, many of which they might find within’ [2].

The entertainments in the arcades ranged in type. While there were more refined shows, such as art shows and elegant balls, displays at the ‘cheap amusement’ end of the spectrum were also found in these buildings, demonstrating the appetite for ‘new and innovative entertainments, many of which utilised new technologies in their presentation’ [3] but might also utilise the fantastical or seemingly strange to amuse patrons. While spectacle was a key component, these amusements might also be considered educative, about current or historic people and events, or new ideas and technologies.

The Queen’s Arcade was a regular site of such amusements, which also might play at other locations around Melbourne and Australia. These included models and panoramas of current events, such as important moments and sites in the war in the Crimea in the mid-1850s, including a model of the Sevastopol and Kronstadt naval bases, as well as St Petersburg. In 1855 and 1858, there featured an ‘exhibition of dissolving views‘ using a calcium light to project photographs, in the first case, including ‘places such as the Arctic regions, Turkey, Italy, Netley Abbey, and Walmer Castle‘, with the commonly applied entry fee of a shilling for adults and children at sixpence.

In the Eastern Arcade in Bourke Street Melbourne, there were a variety of such cheap amusements, as well as businesses that straddled the line between entertainment and health and wellbeing, such as phrenologists and fortune tellers. As these latter characters are the focus of the work of other scholars [4], I’ll focus here on the other amusements present in this building, but in another post, I might talk about these people in other arcades!

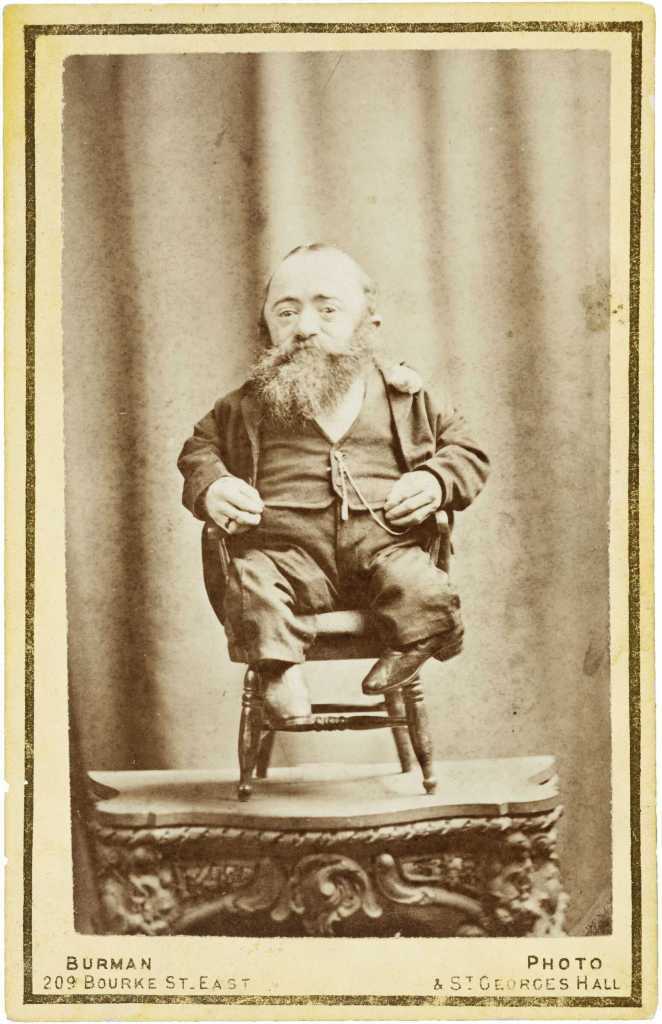

One of the other business-owners in the building also thought of innovative ways to attract people to the building. In 1879 fancy goods dealer Isaac Solomons hosted the Great American Pantechnetha in conjunction with a fancy bazaar, which featured panoramas of ‘the Prussian & Russian wars and views of the principal cities in Europe – surpassing anything ever seen in the Australian colonies’. He also later paid Dominick Sonsee, ‘the smallest man in the world’, to appear and hold an ‘at home’, where he chatted with visitors about politics and current events. Sonsee later, however, took publican Thomas Bentley to court over non-payment of the fee from Solomons, which Bentley had allegedly accepted on Sonsee’s behalf but not passed on, with newspapers rueing that Sonsee had been taken advantage of and portraying him in a pitying light.

Carte de visite advertisement for appearance of Dominick Sonsee at the Eastern Arcade, c1880.

Photographer: William Burman. National Portrait Gallery, 2014.5

The Eastern Arcade also had two dedicated entertainment spaces which featured entertainments such as the US Minstrels and Lady Court Minstrels (the latter also played at the Victoria Arcade & Academy of Music in 1884), and Kate and James Kelly, siblings of bushranger Ned, who held a rather grim entertainment where patrons could see and talk to them for one shilling prior to their brother’s execution in November 1880. In the same arcade in 1914, Seattle-born George and Leo Whitney, who had been leaseholders of Luna Park, Melbourne, opened the Joy Parlour amusement arcade in nine of the arcade shops, ‘entertaining hundreds of people both day and night with all kinds of amusement and picture shows. … Beautifully lit with electric light, and music always‘. According to the oral testimony of George K Whitney, his father (also George) ran the shooting and amusement section of the arcade, while his uncle ran the photography studio, before moving back to the US in the 1920s.

Bourke Street in the area of the arcade was well-established as the heart of Melbourne’s popular entertainment during the late 1800s. The atmosphere was beautifully described around 1912 by future journalist, Hugh Buggy: ‘a non-stop vaudeville show … [with] its music halls or “academies” of music, its billiard parlours, its shooting galleries, and a waxwork chamber of horrors … it was the heart of Theatreland and the stomping ground of sports.'[5] Both the Eastern and the Victoria Arcade and Academy of music on the next block contributed much to this atmosphere. These entertainments and others at the Eastern Arcade show that the life of the surrounding streets entered the once-imagined refined confines of the building and may have contributed (along with larrikins, phrenologists, fortune tellers, theatre connections, and murders) to its poor reputation from the 1890s to 1920s.

Heading north to Brisbane, Henry Morwitch’s Grand Arcade, which seemed to have a regular program of public events, hosting ‘a variety of entertainments and amusements on offer ranging from carnivalesque to the refined’. [6] In 1889, it featured a sideshow-type performer, Fedor Jeftichew, who experienced hypertrichosis, leading to excess body hair, billed as ‘Jo-Jo the Russian dog-faced boy‘. Demonstrating the transnational movements of so many of these entertainers across the globe, Russia-born Jeftichew toured England, Europe and Australia, originally with US showman and circus owner, PT Barnum, who satisfied the public appetite for shows featuring those advertised as ‘monsters’.

Shows that incorporated or featured new technologies also took place in the Grand, including Woodroffe’s glass-blowing exhibition in 1889. Born in the US, Charles Woodroffe exhibited in the States before coming to Australian in the 1860s under the patronage of entertainment entrepreneur George Coppin. Woodroffe’s shows featured glass-blowing combined with technologies such as steam engines made from glass. These shows were popular travelling entertainments and we see Woodroffe exhibiting throughout Australia, as well as presenting his more scientific glass aparatus at international exhibitions. The glassblowing shows were part informative and part show and, as Rebecca C Hopman tells us, ‘delight[ed] spectators with lampworking displays, fabulous models, and tables crowded with glass trinkets’. [7] In 1897 and 1898, new technology again featured, when Lumiére’s cinematograph of moving pictures was exhibited, producing images of the Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee and the Melbourne Cup, as well as ‘other exciting events’.

Like those in Melbourne and Brisbane, Sydney’s arcades also hosted a variety of similar amusements. From October 1893 to around December 1894, the basement of the Strand Arcade played host to the Crystal Maze Palace of Amusement, in the Strand Arcade basement. The newspapers tell us that it included entertainments such as ‘Madame Paula, the scientific palmist’, a mirror maze, and mechanical novelties, gaining ‘a large measure of popularity as a holiday resort‘. The next year the arcade had a model of the Tower of London made entirely of cork (one million pieces!), and from 1896 to 1897, Sawyer’s Australian Waxworks, featuring celebrities of the day such as Sarah Bernhardt. These exhibits attained popularity in the nineteenth-century with contemporary and historical personalities rendered in wax, arguably the most famous today being Madame Tussauds, with branches all over the world (including Sydney). Waxworks seems to have tried to attract broad audiences, being advertised in numerous newspapers, including the Guang yi hua bao/The Chinese Australian Herald.

While these are just a snippet of the types of ‘cheap amusements’ that could be found in the Australian arcades in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they demonstrate the diversity of the types of entertainments that were available. Their presence indicates that arcades were not just sites that would attract the town elites but had a wider class of visitor. While the Eastern Arcade spatially was embedded in Melbourne’s entertainment district, the Strand was in a more apparently refined location on Pitt Street, in the shopping heart of Sydney, although relatively close to the theatre district on King Street. The presence of such amusements widen our understanding not only of the types of businesses found within arcades but also their visitors, breaking down the idea that these buildings were only the preserve of middle-class or elite shoppers and tea-drinkers.

At the same time, these examples also give insight into the global exchanges that took place in the arcades beyond those of commodities. These travelling entertainers often hailed from North America, Europe or Britain, and elsewhere across the the globe, and travelled independently or as part of troupes, sometimes managed by entertainment entrepreneurs such as Coppin or Barnum. They utilised a variety of genres and techniques, including music and dance, as well as technologies driven by steam and electricity [8], wax modelling, and glassblowing in order to amuse and delight their audiences within the arcades.

Learn more

On 31 October 2023, Dr Alexandra Roginski, a fellow Professional Historians Association (Vic & Tas) member, and Professor Andrew Singleton from Deakin University are presenting ‘An Evening of Mystery in the Eastern Arcade: Phrenologists & Spiritualists’ at the Victorian Archives Centre and online. It should be a great talk, so book via Eventbrite! I’m so looking forward to it!

Footnotes

- James Lesh, ‘Cremorne Gardens, Gold-rush Melbourne, and the Victorian-era Pleasure Garden, 1853-63’, Victorian Historical Journal 90.2 (2019): 219–252. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/INFORMIT.893493942124131.

- Nicole Davis, Nineteenth-century Arcades in Australia: History, Heritage & Representation (PhD Thesis, University of Melbourne, 2023), 165.

- Ibid. 186.

- Alexandra Roginski, Science and Power in the Nineteenth-Century Tasman World: Popular Phrenology in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand (Cambridge, 2022), in which she talks about the Eastern Arcade.

- Hugh Buggy, The Real John Wren (Widescope International, 1977), quoted in Otto, Capital, 47–48.

- Davis, ‘Nineteenth-century Arcades in Australia’, 192.

- Rebecca C Hopman, ‘Demonstrations Gain Steam’, Journal of Glass Studies 62 (2020): 281.

- See for example: Henry Reese, ‘”The World Wanderings of a Voice”: Exhibiting the Cylinder Phonograph in Australasia’, in A Cultural History of Sound, Memory, and the Senses, edited by Joy Damousi & Paula Hamilton (Routledge, 2017)

Other Sources & Further Reading

Mimi Colligan, Canvas Documentaries: Panoramic Entertainments. inNineteenth-Century Australia and New Zealand (Melbourne University Press, 2002).

Corning Museum of Glass, ‘The Grand Bohemian Troupe of Fancy Glass Workers|Behind the Glass Lecture’, 19 January 2019. YouTube.

Clay Djubal, ‘What Oh Tonight: The Methodology Factor and Pre-1930s’ Australian Variety Theatre (with Special Focus on the One Act Musical Comedy, 1914–1920)’ (PhD Thesis, University of Queensland, 2005).

Harry Gordon, ‘Buggy, Edward Hugh (1896–1974)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography.

Andrew May, ‘Bourke Street’, eMelbourne: The City Past and Present.

Official Record Containing Introduction, History of Exhibition, Description of Exhibition and Exhibits, Official Awards of Commissioners and Catalogue of Exhibits. (Melbourne: Mason, Firth & McCutcheon, 1882), 434, 648.

Kristin Otto, Capital: Melbourne When it Was the Capital City of Australia, 1901–27 (Text Publishing, 2009), 47–75.

Henry Reese, ‘Spectacular Entertainments at Edison Lane’ (parts one and two), State Library of Queensland Blog, 20 December 2022.

Henry Reese, ‘Settler Colonial Soundscapes: Phonograph Demonstrations in 1890s Australia’, in Phonographic Encounters: Mapping Transnational Cultures of Sound, 1890–1945, edited by Elodie A Roy and Eva Moreda Rodriguez (Routledge, 2022), 60–77.

‘The Great Exhibition, 1851: Philosophical instruments by Deleuil 1851’ [photograph], Claude-Marie Ferrier, RCIN 2800038, Royal Collection Trust.

Richard Waterhouse, ‘The Internationalisation of American Popular Culture in the Nineteenth Century: The Case of the Minstrel Show’ Australasian Journal of American Studies 4.1 (1985): 1–11.

Richard Waterhouse, From Minstrel Shows to Vaudeville: the Australian Popular Stage 1788–1914 (NSW University Press, 1990)

Richard Waterhouse, Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: A History of Australian Popular Culture Since 1788 (Longman, 2005).

Alexa Wright, Monstrosity: The Human Monster in Visual Culture (Bloomsbury, 2013), 84–85.